In the western U.S., millions of acres of perennial grasslands, shrublands, and forests are held in the public domain and managed by state and federal agencies for multiple land uses. Although riparian meadows account for a small percentage of this landscape, their ecological and conservation values are substantial. These ecosystems provide a suite of benefits—including clean water, flood attenuation, nutrient sequestration, wildlife habitat, and livestock grazing. Local ranching communities rely on these systems for summer grazing, and in turn, livestock provide protein to support a growing human population.

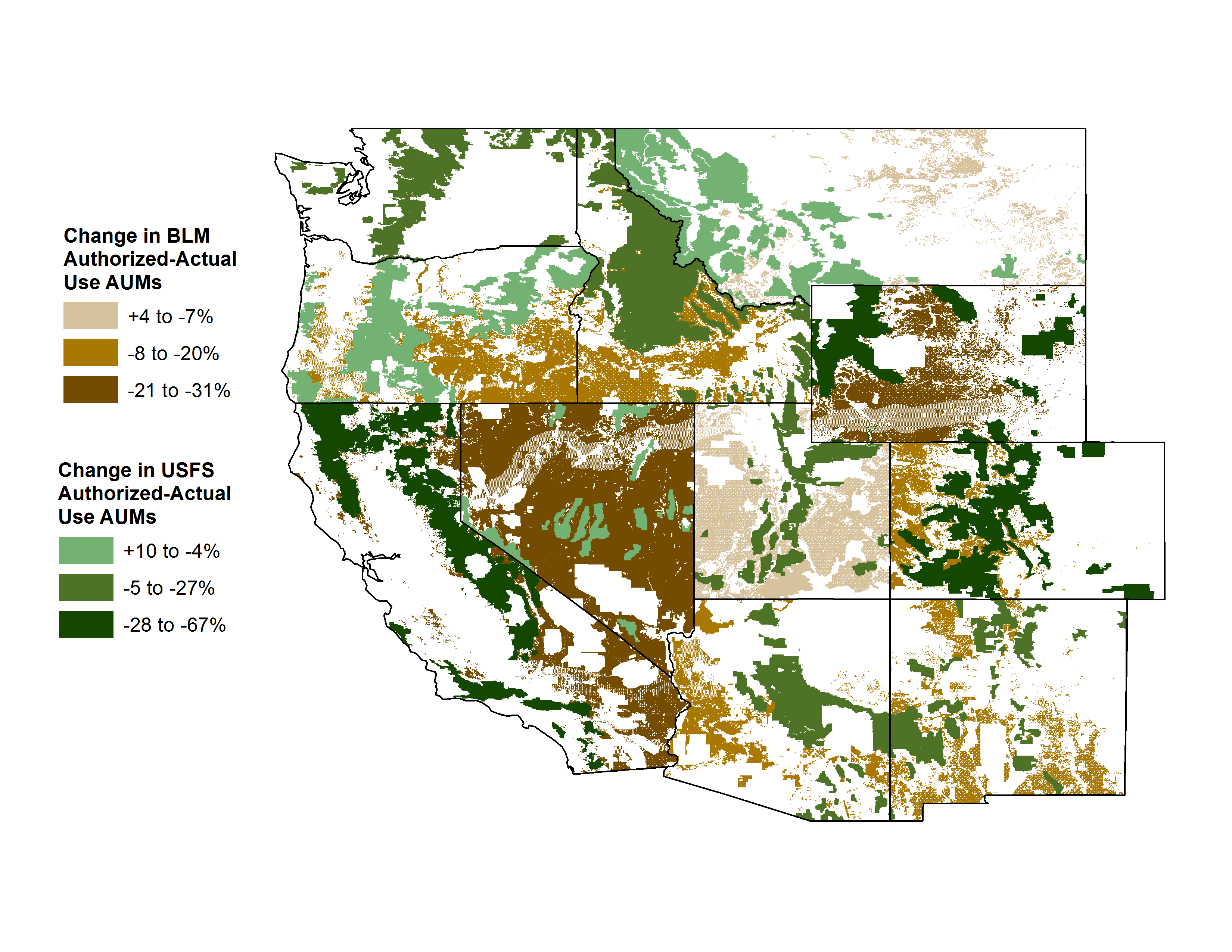

Society has strong contemporary expectations for grazing lands stewardship to balance agricultural goals with social, cultural, and conservation goals. During the 1990s, there was a fundamental policy and management paradigm shift for US federal public lands that initiated the modern grazing management era, in which riparian meadows emerged as critical conservation areas, and production and conservation objectives were co-valued. To meet these new riparian grazing objectives, livestock pressure on western federal lands was considerably reduced (Fig. 1).

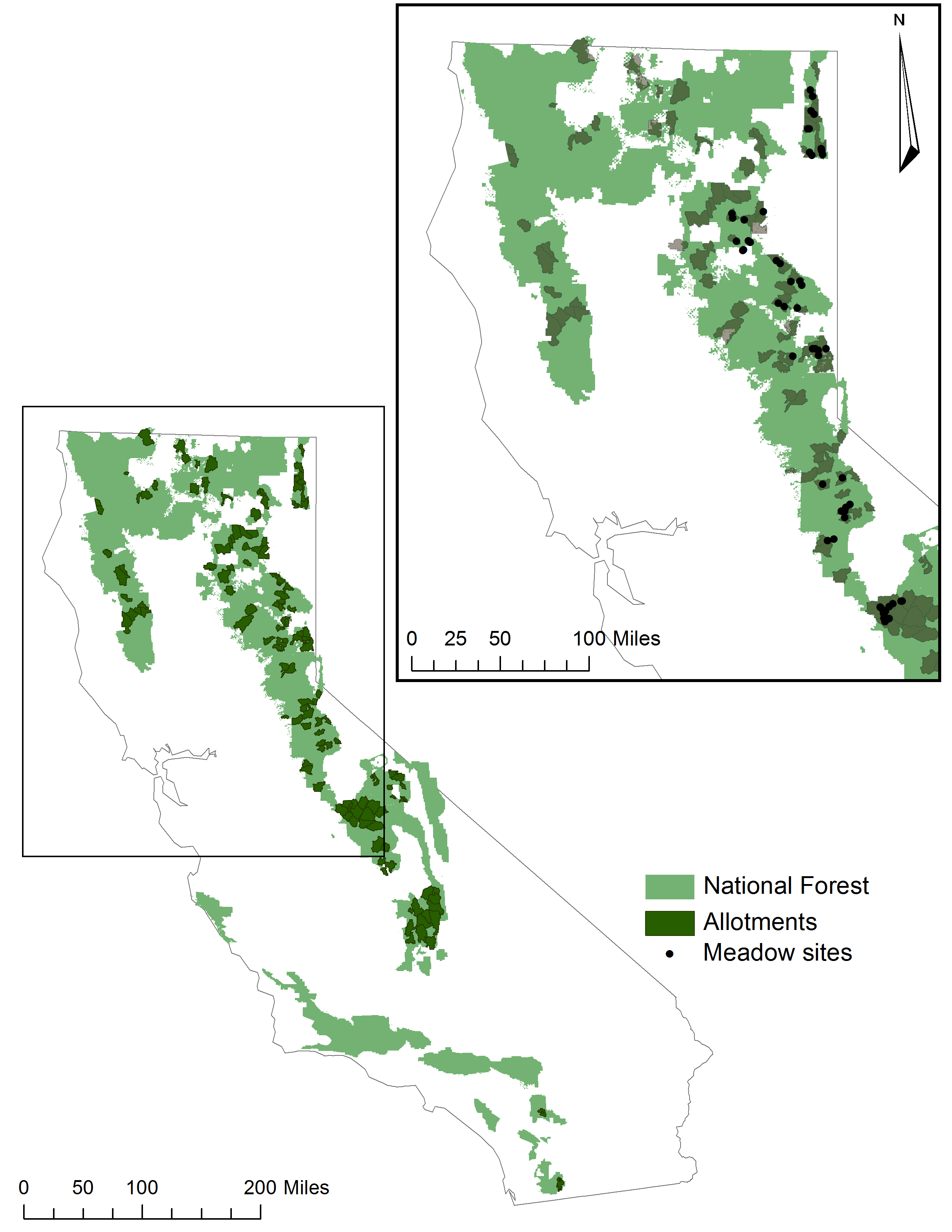

At the start of this modern grazing era, the US Forest Service in California initiated a state-wide, long-term meadow vegetation monitoring program (1) to document baseline conditions prior to the new riparian grazing standards; and (2) to examine subsequent trends in meadow vegetation. The riparian grazing standards implemented by the Forest Service over the past two decades established grazing regimes that are much different than those examined in the 1980s through early 1990s (more information here). UC Rangelands and UC Cooperative Extension collaborated with the Forest Service to examine relationships between long-term (1997–2015) vegetation trends, livestock grazing pressure, and environmental conditions under this modern grazing management (Fig. 2).

Our results suggest reductions in grazing pressure in the modern era have improved the balance between riparian conservation and livestock production goals. Overall, plant species richness and diversity increased over the study period, which were driven by increases in native forbs. Changes in plant community were not associated with either grazing pressure or precipitation at the grazing allotment scale (the administrative scale); however, both grazing pressure and precipitation had significant, yet modest, associations with changes in plant community at the meadow site scale. It is important to note that changing climate conditions (reduced snowpack, changes in timing of snowmelt) could trigger shifts in plant communities, potentially impacting both conservation and agricultural outcomes. Therefore, adaptive, site-specific management strategies are required to meet grazing pressure limits and safeguard ecosystem services within individual meadows, especially under more variable climate conditions.

To read the recently published paper, click here!